All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The gvhd Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the gvhd Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The gvhd and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The GvHD Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Medac and supported through grants from Sanofi and Therakos. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View GvHD content recommended for you

ECP: Clinical considerations for the treatment of cGvHD

Do you know... Which patients are not eligible to receive extracorporeal photopheresis as a second-line therapy of steroid-refractory chronic GvHD?

First studied in chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGvHD) over 30 years ago, extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) is now a well-established second-line treatment option for patients with GvHD who have become steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent.1 Though various other second-line treatments have also been explored, they are not as effective in controlling GvHD activity and are accompanied by serious adverse events. Whereas, in the absence of severe systemic immunosuppression, ECP is effective and exhibits a preferable safety profile for the treatment of GvHD. Furthermore, ECP is currently being investigated as a potential treatment option for GvHD prophylaxis.

At present, there are two different methods established for the ECP procedure, the open/off-line method and the closed system/in-line method; the latter is a ‘1-step method’, that consists of kits and applied drugs, and has been approved in many countries. Here, we summarize key considerations of ECP, using the closed system for the treatment of patients with cGvHD.

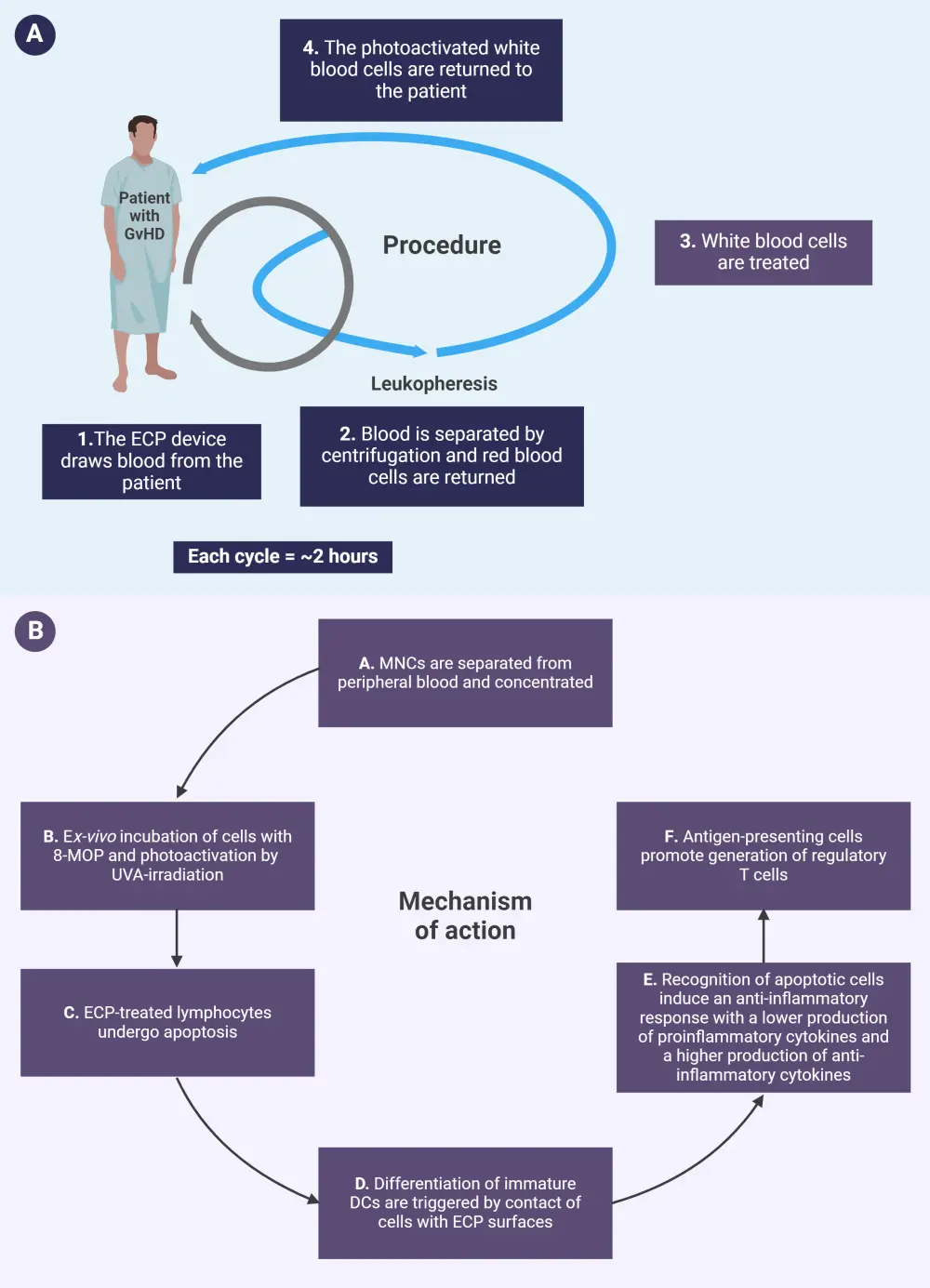

ECP: procedure and mechanism of action

Recent observations in molecular biology have led to a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanism of action of ECP.1 Blood is collected from patients via either the peripheral vein or a permanently implanted catheter and is then centrifuged to remove mononuclear cells.2,4 After this, cells are treated with 8-methoxypsoralen (8-MOP) and exposed to ultraviolet-A light.2 During this stage, three main processes occur which are:1

- 8-MOP induced apoptosis;

- monocyte-to-dendritic cell differentiation and cytokine profile; and

- T-cell subpopulation modifications.

The patient is then reinfused with the irradiated cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The A procedure and B mechanism of action of ECP*

DC, dendritic cell; ECP, extracorporeal photopheresis; 8-MOP, 8-methoxypsoralen; MNC, mononuclear cell; UVA, ultraviolet-A.

*Adapted from Drexler, et al.2 and Knobler, et al.3 Created with BioRender.com

Patient selection3

According to current guidelines, patients with moderate-to-severe cGvHD should receive systemic therapy. Although there is no generally acknowledged definition of steroid-refractory cGvHD, it is widely accepted that this can be defined as progression on prednisone treatment at 1 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks, or stable disease while receiving prednisone at ≥0.5 mg/kg/day for 4─8 weeks. Patients who have cGvHD and are unable to taper steroid treatment, have recurrent infections, or have a high risk of relapse of their underlying disease, are eligible to receive ECP as a second-line therapy.

Patients who are exempt from receiving ECP as a second-line therapy are those with total leucocyte counts below 1.0 G/L, intolerance to 8-MOP, heparin, or citrate products, and hemodynamic instability due to ongoing life-threatening infections or severe bleeding events.

Treatment of cGvHD

Recently, ruxolitinib has become a prominent treatment for steroid-refractory and steroid-dependent cGvHD; however, in comparison with ECP, there are serious adverse effects associated with ruxolitinib treatment. In a study that compared the use of ruxolitinib and ECP, at Day +180 after treatment, the odds ratio in the ruxolitinib group was greater than the ECP group in achieving an overall response of 1.35 (95% confidence interval [CI], p = 0.43).10 However, there were no significant differences observed in progression-free survival, non-relapse mortality, or relapse incidence.10 Additionally in another study, patients with cGvHD were treated with ruxolitinib plus ECP. Increased response rates were observed when a combination was used, 57%, 63%, and 74% overall responses during ECP monotherapy, ruxolitinib monotherapy, and ECP plus ruxolitinib, respectively.1 Studies that used ECP as a second-line treatment of cGvHD are summarized below in Table 1 (response assessment was not uniform across all studies).2

Table 1. Results with second-line treatment of cGvHD with ECP*

|

Author |

Patients, n |

CR/PR skin, |

CR/PR liver, % |

CR/PR oral, % |

ORR, % |

OS, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Greinix, et al.13 |

15 |

100 |

90 |

100 |

93 |

93 |

|

Salvaneschi, et al.14 |

14 |

83 |

67 |

67 |

64 |

79 |

|

Seaton, et al.15 |

28 |

48 |

32 |

21 |

36 |

86 |

|

Apisarnthanarax, et al.16 |

32 |

59 |

— |

— |

56 |

59 |

|

Foss, et al.17 |

25 |

64 |

0 |

46 |

64 |

60 |

|

Rubengni, et al.18 |

32 |

81 |

77 |

92 |

69 |

— |

|

Greinix5 |

47 |

93 |

84 |

95 |

83 |

89 |

|

Couriel, et al.6 |

71 |

57 |

71 |

78 |

61 |

18 |

|

Kanold, et al.19 |

15 |

75 |

82 |

86 |

73 |

67 |

|

Perseghin, et al.20 |

25 |

80 |

67 |

78 |

80 |

76 |

|

Flowers, et al.7 |

48 |

40 |

29 |

53 |

— |

98 |

|

Dignan, et al.8 |

69 |

92 |

— |

91 |

79 |

72 |

|

Greinix, et al.21 |

29 |

31 |

50 |

70 |

31 |

100 |

|

Del Fante, et al.22 |

88 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Hautmann, et al.23 |

32 |

59 |

100 |

60 |

44 |

66 |

|

Malagola, et al.24 |

49 |

33, CR for all manifestations |

— |

— |

||

|

Cid, et al.25 |

26 |

— |

— |

— |

77 |

61 |

|

cGvHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; CR, complete response; ECP, extracorporeal photopheresis; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PR, partial response. |

||||||

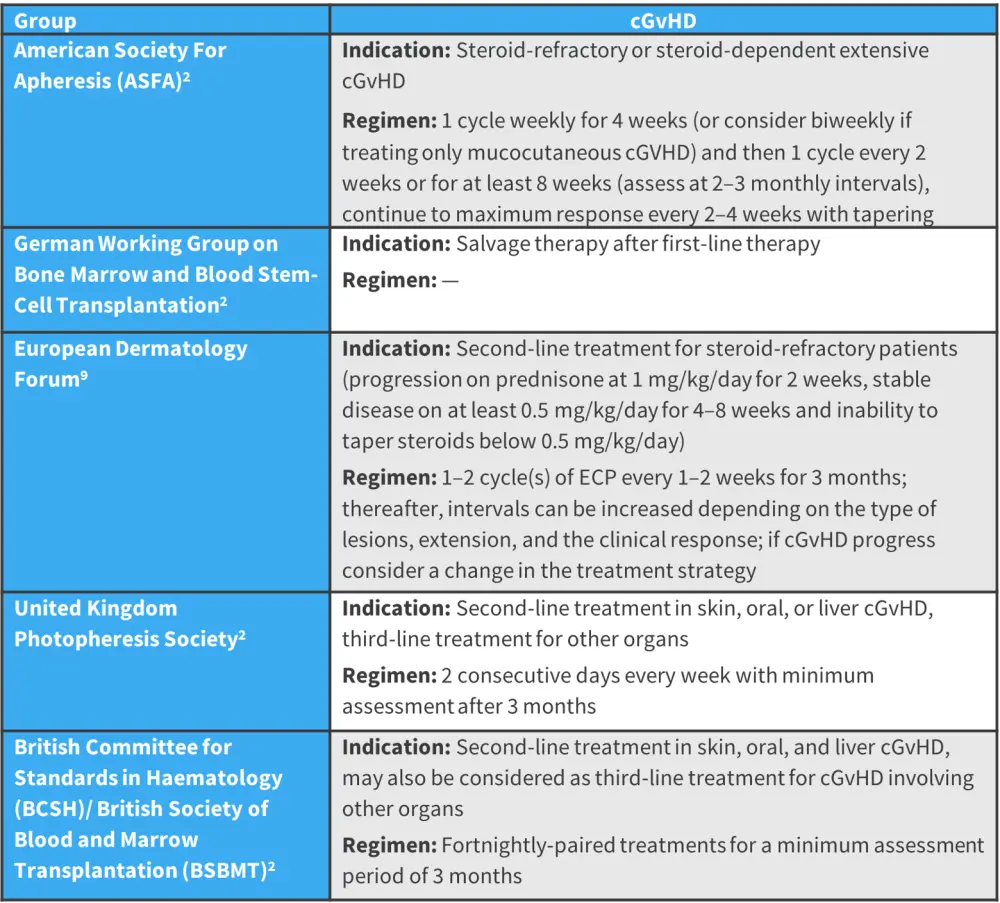

Most of the available data on the efficacy of ECP in cGvHD comes from uncontrolled clinical trials or retrospective studies.2 As a result, determining an ideal treatment schedule for cGvHD has not yet been established.2 Figure 2 summarizes varying recommendations for ECP regimens for the treatment of cGvHD by expert groups.

Figure 2. Expert recommendation on the treatment indications and regimens of ECP*

cGVHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; ECP, extracorporeal photopheresis.

*Adapted from Drexler, et al.2 and Knobler, et al.9

It is important to note that ECP is a more expensive treatment option for patients with cGvHD than the other second-line standard-of-care treatment options.11 The cost of ECP treatment also means it may not be as easily available to patients in contrast with other standard-of-care treatment options. However, from a study conducted over 10 years ago, it was also observed that patients, who received ECP treatment, reported that they had a slightly improved quality of life compared with standard-of-care treatment.11

Safety considerations1,2

During ECP, patients may rely on heparin for anticoagulation which can play a role in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and present challenges to patients with a high bleeding risk and active bleeding due to its long half-life. In general, ECP therapy has not been associated with serious adverse events and typically has an overall favorable safety profile in comparison with other treatment options.

Overall, the main side effect associated with ECP, though mild, is patients may experience increased photosensitivity from 8-MOP. Patients have also reported side effects from repeated peripheral venous puncture or long-term venous access, which include local hematoma, arterial puncture phlebitis, venous thromboembolism, catheter-related infection, and pneumothorax. Additionally, due to the volume of blood required for ECP treatment, patients may also experience hypotension during the treatment procedure. Also, it is important to consider that additional care may be required for patients with cGvHD, areas of supportive care include, but are not limited to:

- prevention of osteoporosis;

- psychological support;

- dietary support;

- rehabilitation;

- prophylaxis of infections; and

- vaccinations (no live vaccinations for Streptococcus pneumoniae and influenza).

Conclusion

In order to treat GvHD, multiple second-line therapies have been explored, though these are not always able to control GvHD effectively and come with multiple side effects.2 ECP is successfully used as a second-line therapy for cGvHD and displays favorable efficacy outcomes and safety profile; however, more clinical trials are required to classify ECP among other available treatment options for patients with cGvHD.1

It is important to consider that the poor prognosis of cGvHD paired with insufficient clinical data for ECP means an optimal treatment regimen has not yet been established. Challenges in determining an ideal treatment schedule may also be due to the frequency and interval of ECP treatment which are heavily dependent on the patient’s follow-ups and the capacity of the apheresis unit, personnel, and reimbursement.2 Furthermore, the use of biomarkers may provide a greater understanding of the immunomodulatory mechanism of ECP which may, in turn, help determine the optimal time to use ECP in clinical practice.12

Despite ECP displaying favorable safety and efficacy outcomes when used as a therapy for patients with GvHD, the lack of an optimal treatment strategy means ECP is not yet widely used in this indication. It is important to note that technical innovations are making ECP accessible to a broader range of patients; however, further efforts are still required to explore potential modifications of the ECP procedure to increase its efficacy.1,2

This educational resource is independently supported by Mallinckrodt. All content is developed by SES in collaboration with an expert steering committee; funders are allowed no influence on the content of this resource.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content