All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The gvhd Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the gvhd Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The gvhd and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The GvHD Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Medac and supported through grants from Sanofi and Therakos. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View GvHD content recommended for you

Use of PTCy in GvHD prophylaxis: Findings from a prospective and a retrospective study

Do you know... A novel regimen of low-dose PTCy + low-dose antithymocyte globulin (ATG) was explored in a recent study by Zu, et al.1 in HLA-matched unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Which of the following outcomes was significantly different between the low-dose PTCy + ATG group and the standard ATG group?

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is used in many hematologic malignancies as a curative approach, but its major limitation is graft-versus-host disease (GvHD).1 Posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy), since its introduction in 2008, has been increasingly used as a GvHD prophylaxis in patients undergoing haploidentical transplantation.2

Evidence from several large retrospective studies demonstrates that PTCy has excellent outcomes in GvHD prophylaxis and in reducing non-relapse mortality (NRM) in the haploid HSCT setting. The GvHD Hub has previously reported developments in the use of PTCy in different patient populations, including those undergoing human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical sibling, and matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplantation.

Here, we provide an update on the use of PTCy as GvHD prophylaxis from two recent studies; the first by Zu, et al.1, published in Bone Marrow Transplantation, that investigated the use of low-dose PTCy with low-dose antithymocyte globulin (ATG); and the second by Saliba, et al.2, published in Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, which investigated whether in patients with GvHD, organ distribution and severity are different after haploidentical (haplo)/PTCy versus MUD/conventional transplantation with or without ATG.

Low-dose PTCy and ATG1

The use of ATG in a GvHD prophylaxis regimen has been associated with an increased risk of infection. To reduce this risk while achieving a good therapeutic effect, low-dose ATG and low-dose PTCy regimens have been used successfully. However, there is no consensus on the optimal dose used for this protocol; therefore, Zu, et al. set out to explore this further in the 10/10 HLA MUD setting.

Study design

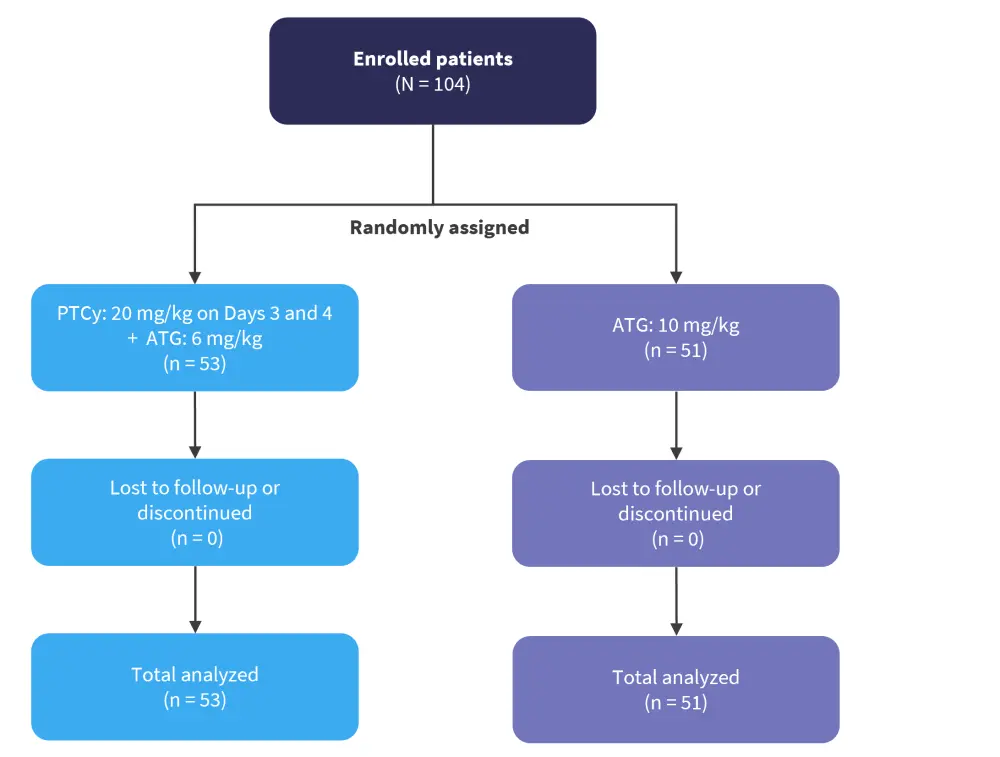

This was a prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial (ChiCTR2200056979) to improve the efficiency of GvHD prophylaxis using low-dose PTCy combined with low-dose ATG in patients with hematologic malignancies in their first complete remission and undergoing the first 10/10 HLA MUD peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to either a low-dose PTCy + ATG group or a standard ATG group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study design*

ATG, antithymocyte globulin; PTCy, posttransplant cyclophosphamide.

*Adapted from Zu, et al.1

The outcomes of interest included engraftment, acute GvHD (aGvHD), chronic GvHD (cGvHD), NRM, GvHD-free, relapse-free survival (GRFS), and infectious complications.

Baseline characteristics

A total of 104 patients were included, with a median age of 29 years (range, 2–59 years) and 59% of patients were male. In the standard ATG group, 60.8% of patients were diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, 31.4% with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and 7.8% with myelodysplastic syndromes, compared with 45.3%, 41.5%, and 11.3%, respectively, in the PTCy + ATG group. The percentages of patients with high-risk disease (50.9% vs 39.2%) and negative minimal residual disease (56.6% vs 52.9%) were higher in the PTCy + ATG group compared to the ATG group. The median follow-up was 561 days and 600 days in the low-dose PTCy + ATG group and ATG group, respectively.

Engraftment, aGvHD, cGvHD, NRM, and GRFS

Engraftment was achieved in all patients in the low-dose PTCy + ATG group, while two patients had primary graft failure in the ATG group. The median time to neutrophil and platelet recovery was shorter in the low-dose PTCy + ATG group compared with the ATG group: 12 days vs 13 days (p = 0.001) and 12 days vs 14 days (p = 0.002), respectively.

With regards to Grade 2−4 aGvHD, the 100-day cumulative incidence (CI) was significantly lower in the low-dose PTCy + ATG group compared with the ATG group (24.5% vs 47.1%; p = 0.017). There was no significant difference between CI of grade 3−4 aGvHD between groups (p = 0.204) and as no patients experienced late onset aGvHD there was no difference between CI of aGvHD at day +100 and day +180. Similarly, the 2-year CI of cGvHD was significantly lower in the low-dose PTCy + ATG group compared with the ATG group (14.1% vs 33.3%; p = 0.013). Interestingly, the rates of moderate to severe cGvHD at 2 years remained comparable between the two groups (8.0% vs 15.7%; p = 0.207).

Patients in the low-dose PTCy + ATG group also showed a lower CI of NRM (13.2% vs 34.5%; p = 0.049) and significantly improved GRFS at 2 years (67.3% vs 42.3%; p = 0.032) compared with patients in the ATG group.

Infections

The incidence of infectious complications was significantly increased in the ATG group compared with the PTCy-ATG group, for the three following categories:

- Pulmonary infections, 58.8% vs 35.8% (p = 0.019)

- Hemorrhagic cystitis, 62.7% vs 37.7% (p = 0.011)

- Epstein-Barr virus, 60.8% vs 15.1% (p < 0.0001)

PTCy compared with conventional GvHD prophylaxis2

While PTCy has consistently been shown to reduce the incidence of both aGvHD and cGvHD, the way different organs are impacted by this treatment compared with conventional GvHD prophylaxis is not known.

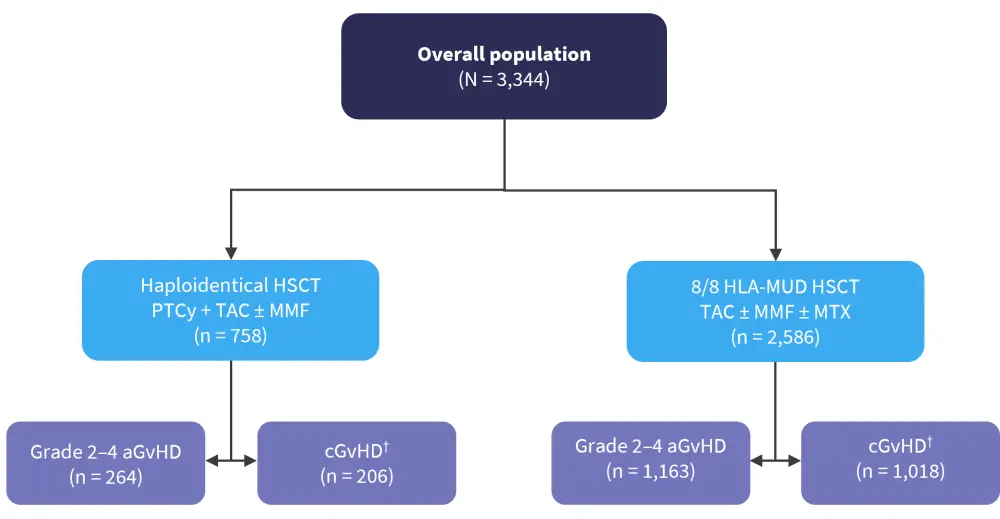

Saliba, et al.2 performed a retrospective cohort study assessing the organ manifestations in patients after haplo-PTCy-based GvHD prophylaxis (PTCy, calcineurin inhibitor + mycophenolate mofetil) compared with patients after HLA-MUD + conventional prophylaxis (calcineurin inhibitor + methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil) with or without ATG between 2013 and 2017. The data for the overall cohort were derived from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) database, and patients were grouped into two separate, but not mutually exclusive cohorts: a cohort of patients with Grade 2−4 aGvHD and a cohort of patients with de novo, progressive, or relapsing cGvHD (Figure 2). Conditioning regimens included myeloablative or reduced intensity/non-myeloablative, with or without total body irradiation.

The primary endpoints were GvHD organ manifestations and severity, NRM, and overall survival (OS) in patients with Grade 2−4 aGvHD or cGvHD, and cGvHD in patients with Grade 2–4 aGvHD.

Figure 2. Study design*

aGvHD, acute graft-versus-host disease; cGvHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; MUD, matched unrelated donor; PTCy, posttransplant cyclophosphamide; TAC, tacrolimus.

*Adapted from Saliba, et al.2

†Includes de novo, progressive, or relapsing cGvHD.

Results

Overall cohort

The 6-month CI of Grade 2−4 aGvHD was lower in patients in the haplo-PTCy group compared with those in the MUD/conventional group (35% vs 42%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.8; p = 0.001). The 2-year CI of cGvHD was significantly lower after the haplo-PTCy transplantation than after the MUD/conventional transplantation without ATG (HR, 0.6; p < 0.001).

aGvHD and cGvHD cohorts

A total of 1,427 and 1,224 patients with Grade 2−4 aGvHD and cGvHD, respectively, were included. In the aGvHD cohort, patients in the haplo-PTCy subgroup had younger recipients, a higher disease risk index, a higher proportion of bone marrow grafts, and a higher proportion of total body irradiation-based regimens compared with patients in the MUD/conventional subgroup (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics*

|

aGvHD, acute graft-versus-host disease; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; cGvHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; CI, cumulative incidence; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; DRI, disease risk index; F, female; haplo, haploidentical; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; M, male; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; MUD, matched unrelated donor; NMC, non-myeloablative conditioning; PB, peripheral blood; PTCy, posttransplant cyclophosphamide; TBI, total body irradiation. |

||||||

|

Characteristic, % (unless otherwise stated) |

aGvHD cohort |

cGvHD cohort |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Haplo-PTCy |

MUD/ conventional |

p value† |

Haplo-PTCy |

MUD/ conventional |

p value† |

|

|

Recipient age, years |

— |

— |

<0.001 |

— |

— |

<0.001 |

|

18–39 |

31 |

15 |

— |

26 |

16 |

— |

|

40–59 |

34 |

31 |

— |

40 |

30 |

— |

|

≥60 |

35 |

54 |

— |

34 |

54 |

— |

|

Median HSCT-CI score (range) |

3 |

3 |

0.5 |

2 |

3 |

0.03 |

|

Median donor age, years |

39 |

28 |

<0.001 |

37 |

28 |

<0.001 |

|

Donor-recipient sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

M-M |

38 |

46 |

— |

35 |

44 |

— |

|

M-F |

27 |

26 |

— |

28 |

26 |

— |

|

F-M |

20 |

13 |

0.01 |

18 |

15 |

— |

|

F-F |

15 |

13 |

— |

18 |

13 |

— |

|

Disease |

— |

— |

<0.001 |

— |

— |

<0.001 |

|

AML |

61 |

44 |

— |

58 |

46 |

— |

|

ALL |

19 |

12 |

— |

23 |

12 |

— |

|

CML |

4 |

2 |

— |

4 |

2 |

— |

|

MDS |

16 |

42 |

— |

15 |

39 |

— |

|

DRI |

— |

— |

0.003 |

— |

— |

0.003 |

|

Low |

10 |

5 |

— |

9 |

5 |

— |

|

Intermediate |

48 |

46 |

— |

59 |

54 |

— |

|

High |

36 |

44 |

— |

29 |

38 |

— |

|

Graft type |

— |

— |

<0.001 |

— |

— |

<0.001 |

|

BM |

35 |

16 |

— |

31 |

14 |

— |

|

PB |

65 |

84 |

— |

69 |

86 |

— |

|

Conditioning intensity |

— |

— |

<0.001 |

— |

— |

<0.001 |

|

MAC/TBI |

27 |

12 |

— |

23 |

11 |

— |

|

MAC/no TBI |

22 |

37 |

— |

22 |

38 |

— |

|

NMC |

51 |

50 |

— |

55 |

51 |

— |

|

Median follow-up in survivors, months |

24 |

34 |

— |

21 |

27 |

— |

|

aGvHD grade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3–4 |

28 |

39 |

0.001 |

— |

— |

— |

|

1–4 |

— |

— |

— |

75 |

69 |

0.02 |

|

Interval between transplant and GvHD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Median, |

35 |

33 |

0.006 |

— |

— |

— |

|

>Day 100 |

4 |

6 |

0.2 |

— |

— |

— |

The most common organs involved in both groups in the aGvHD cohort was skin (64–67%) and lower gastrointestinal tract (52–55%). Patients in the haplo-PTCy group showed a lower occurrence of severe lower gastrointestinal aGvHD compared with the MUD/conventional group with ATG (p = 0.05) or without ATG (p = 0.001). Both haplo-PTCy groups also showed less involvement of the upper gastrointestinal tract (p = 0.03) and liver (p = 0.04) compared with the MUD/conventional transplantation without ATG.

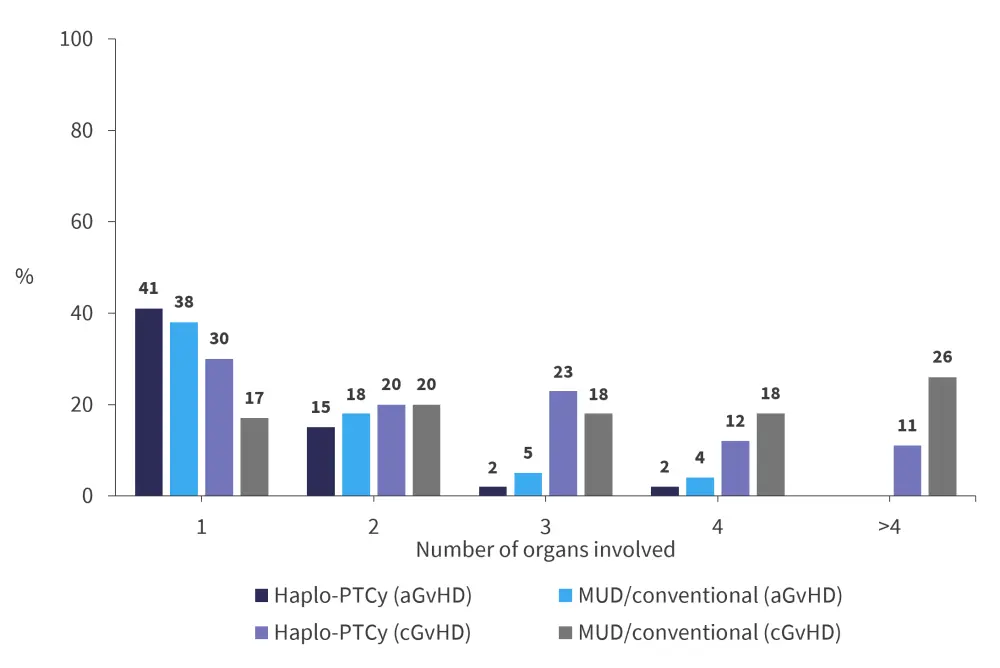

In the cGvHD cohort, patients in the haplo-PTCy subgroup showed less involvement of the gastrointestinal tract (p = 0.001), mouth (p < 0.001), eyes (p < 0.001), liver (p < 0.001), lungs (p = 0.01), musculoskeletal organs (p < 0.001), and “other” organs (p = 0.01) compared to the MUD/conventional subgroup. However, the genitourinary involvement was more common after the haplo-PTCy transplantation with peripheral blood (p = 0.01), and patients in this group were also less likely to have ≥2 visceral organs involved. Patients in the haplo-PTCy group were significantly less likely to have ≥2 visceral organs involved compared to patients undergoing the MUD-conventional transplantation without ATG (p < 0.001). The number of organs involved in both aGvHD and cGvHD cohorts is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Number of organs involved in the aGvHD and cGvHD groups*

aGvHD, acute graft-versus-host disease; cGvHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; MUD, matched unrelated donor; PTCy, posttransplant cyclophosphamide.

*Adapted from Saliba, et al.2

In the aGvHD cohort, the median follow-up duration was 24 months (range, 2.6–62 months) in the haplo-PTCy subgroup and 34 months (range, 1–66 months) in the MUD/conventional subgroup.

The multivariate analysis showed that the NRM was lower (HR, 0.6; p = 0.01) in the haplo-PTCy group compared to the MUD/conventional group in transplants that were not from a female donor to a male recipient. The OS was comparable after haplo-PTCy versus MUD/conventional transplantation + ATG (HR, 1.05; p = 0.7) and the MUD/conventional transplantation − ATG (HR, 0.8; p = 0.1). Patients in the haplo-PTCy group receiving non-myeloablative conditioning showed a lower cGvHD rate compared to the MUD/conventional transplantation − ATG (HR, 0.4; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariate analysis: cGvHD in patients with Grade 2–4 aGvHD*

|

ATG, antithymocyte globulin; cGvHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; MUD, matched unrelated donor; PTCy, posttransplant cyclophosphamide. |

||||

|

cGvHD |

Overall |

p value† |

≥60 years |

p value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Non-MAC |

||||

|

MUD/conventional |

1.0 |

— |

1.0 |

— |

|

MUD/conventional |

0.5 (0.3–0.6) |

<0.001 |

0.5 (0.4–0.7) |

<0.001 |

|

Haplo-PTCy-based prophylaxis |

0.4 (0.3–0.6) |

<0.001 |

0.4 (0.2–0.6) |

<0.001 |

|

MAC |

||||

|

MUD/conventional |

1.0 |

— |

1.0 |

— |

|

MUD/conventional |

0.6 (0.4–0.8) |

0.001 |

0.7 (0.4–1.3) |

0.3 |

|

Haplo-PTCy-based prophylaxis |

0.9 (0.7–1.3) |

0.9 |

1.3 (0.5–3.2) |

0.5 |

Among surviving evaluable patients, the median follow-up after cGvHD diagnosis was 21 months (range, 0.23–56 months) in the haplo-PTCy group, 26 months (range, 0.23–58 months) in the MUD/conventional transplantation + ATG group, and 27 months (range, 0.33–63 months) in the MUD/conventional transplantation – ATG group.

The multivariate analysis showed that the NRM was lower after haplo-PTCy versus MUD/conventional transplantation (HR, 0.6; p = 0.04). The multivariate analysis also showed that the OS within the first 6 months after the cGvHD diagnosis, was significantly lower in the haplo-PTCy group versus the MUD/conventional transplantation group (HR, 1.6; p = 0.03). However, the OS was comparable between the two groups after 6 months (HR, 0.9; p = 0.6), irrespective of the use of ATG in the MUD/conventional transplantation group.

Conclusion

The study by Zu, et al.1 shows the potential of low-dose PTCy + ATG-based GvHD prophylaxis as a future strategy for GvHD treatment in patients in their first complete remission after HLA-MUD peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. On the other hand, Saliba, et al.2 focused on organ manifestations related to haplo-PTCy GvHD prophylaxis. Furthermore, the study showed that lower gastrointestinal tract aGvHD and cGvHD were less common with the haplo-PTCy prophylaxis, as well as a lower NRM. The studies have several limitations, such as having a small number of HLA-matched transplants, a short follow-up, the existence of differences in medical practices, and one study being retrospective in nature, which all warrants further research. Nevertheless, these studies will inform further optimization of PTCy-based GvHD prophylaxis.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

Which consideration most strongly guides your decision to escalate therapy in SR-aGvHD?