All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The gvhd Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the gvhd Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The gvhd and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The GvHD Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Medac and supported through grants from Sanofi and Therakos. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View GvHD content recommended for you

Editorial theme | Infection prophylaxis in pediatric and adult patients receiving HSCT

Do you know... In a retrospective study by Gardener et al., there was no significant difference between patients receiving levofloxacin prophylaxis post-HSCT and those who did not for which outcome?

Introduction

Infections in patients who receive a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are a major cause of morbidity.1 Infection prophylaxis can be used in the pre-engraftment phase of HSCT to minimize the risk of bacteremia and viremia; however, this practice is not standardized.2

Infection prophylaxis has been previously associated with certain risks, such as antibiotic resistance and disruption of the gut microbiome, which could lead to an increase in acute graft-versus-host disease (aGvHD).1 In addition, there may be an increased risk for Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) infection in patients who receive prophylaxis, although this could be due to other factors including immunosuppression and long-term antibiotic use.

Here, we will discuss three publications about the effect of prophylaxis on rates of bacteremia, C. diff infection, and viral reactivation. This is the second article in our editorial theme series on supportive care, with our previous article focusing on nutritional support for improved clinical outcomes post-HSCT.

Bacterial prophylaxis

Levofloxacin2

In a retrospective study by Gardener et al.,2 outcomes were measured in patients who received levofloxacin prophylaxis post-HSCT, compared with patients who did not receive levofloxacin, between 2016 and 2020. All patients had access to other antibiotics if required. For example, if patients receiving levofloxacin required a broad-spectrum antibiotic, levofloxacin was discontinued then restarted after antibiotic therapy.

In total, 370 patients receiving 443 HSCTs were included in the study, with 227 and 216 HSCTs including levofloxacin prophylaxis and not including levofloxacin prophylaxis, respectively. This study included both pediatric and adult patients, with a median age of 6.7 years (range, 0.5–39 years).

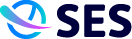

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who experienced >1 bacterial bloodstream infection in the first 100 days posttransplantant (Figure 1). Secondary outcomes included incidence of C. diff infections, aGvHD, and death within the first 100 days and 12 months posttransplant.

Figure 1. Incidence of infections*

C. diff, clostridioides difficile.

*Adapted from Gardener, et al.2

Rates of bacterial bloodstream and C. diff infections were found to be significantly increased in patients who did not receive levofloxacin prophylaxis.

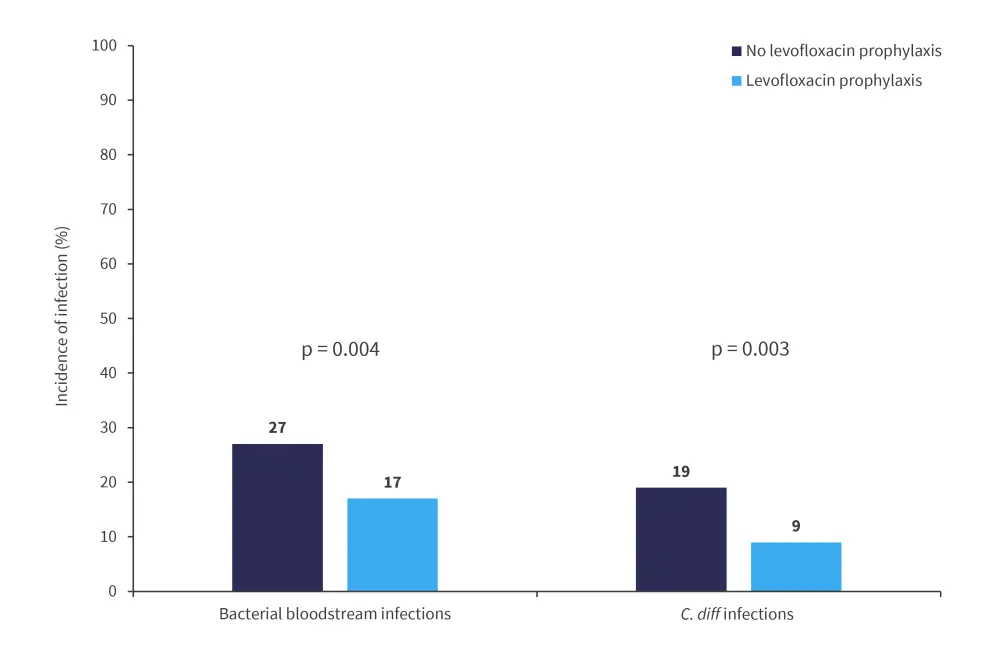

Although death rates were higher in both the first 100 days and first 12 months post-HSCT in patients who did not receive levofloxacin prophylaxis, this difference was not found to be significant (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Incidence of death*

HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

*Adapted from Gardener, et al.2

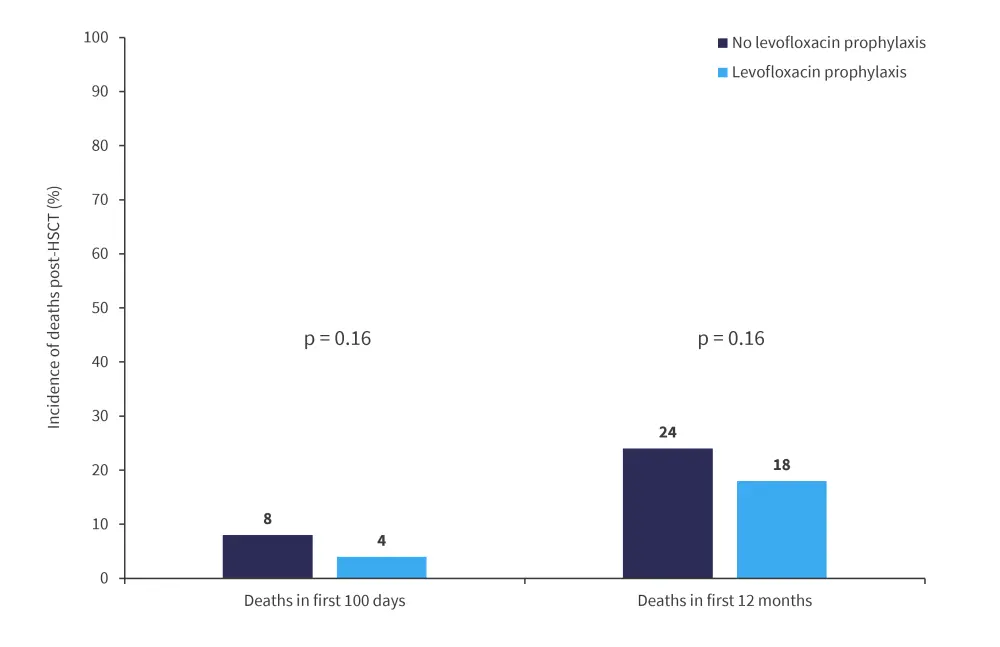

Other outcome measures, including non-relapse mortality and incidence of fungal infections, are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Other outcome measures*

aGvHD, acute graft-versus-host disease; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; MDRO, multi-drug resistant organism.

*Adapted from Gardener, et al.2

The incidence of aGvHD was significantly higher in patients who did not receive levofloxacin compared to those who did, suggesting use of levofloxacin as a prophylactic does not increase GvHD risk.

Cefepime and other antibiotics1

Alrugaib et al. conducted a retrospective study in pediatric patients (<14 years of age) who had received HSCT and bacterial prophylaxis between 2015 and 2018. This study aimed to evaluate the rates of bacteremia and C. diff infections in patients receiving prophylaxis, compared with previously published data. Bacteremia has been reported to occur in around 11–43.4% of pediatric patients receiving a HSCT.

Patients received either

- cefepime 50 mg/kg/dose every 8 hours (intravenous);

- ciprofloxacin 15–20 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours (oral); or

- ciprofloxacin 10 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours (intravenous) if allergic to penicillin.

Prior to 2016, patients received piperacillin and tazobactam instead of cefepime.

This study included 123 patients who received a total of 135 HSCTs. In terms of bacteremia and associated complications,

- 77% of patients received cefepime prophylaxis;

- 21% received piperacillin and tazobactam; and

- 1.4% received ciprofloxacin.

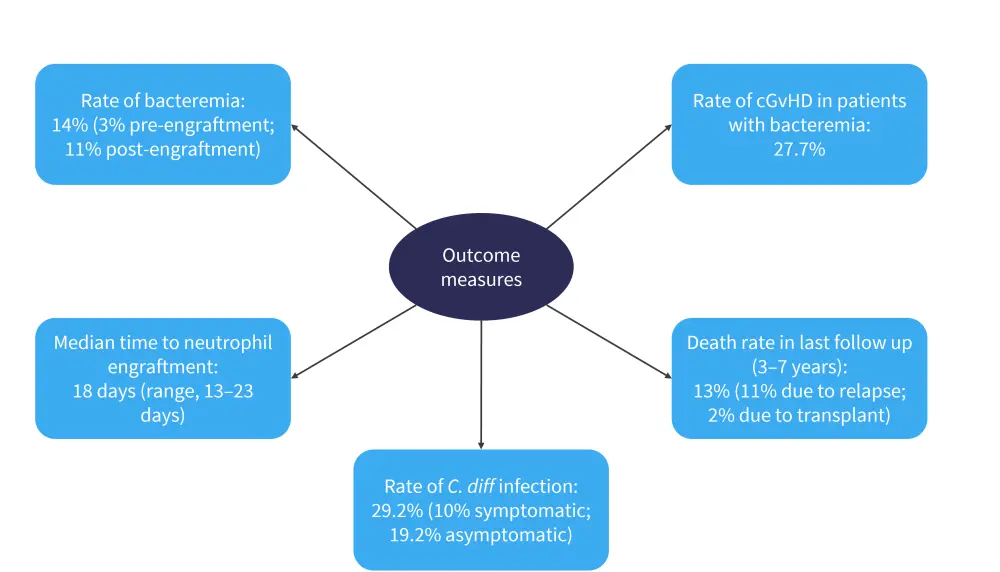

Primary and secondary outcome measures are shown in Figure 4, including the primary endpoint: rate of bacteremia. The rate of bacteremia was significantly higher in patients who received piperacillin and tazobactam compared with cefepime, which prompted the decision to change patients to cefepime in 2016.

Figure 4. Primary and secondary outcome measures*

C. diff, clostridioides difficle; cGvHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease.

*Adapted from Alrugaib, et al.1

The study was limited by its small sample size and fact that all patients received transplants at one center. However, it demonstrates that prophylaxis with cefepime lowers the risk of bacteremia while not increasing the risk of C. diff infections.

Viral prophylaxis

Letermovir3

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) can reactivate after allogeneic HSCT, which is associated with a risk of aGvHD and can cause increased transplant-related mortality among patients. For this reason, prevention of CMV after transplant is essential for effective treatment.

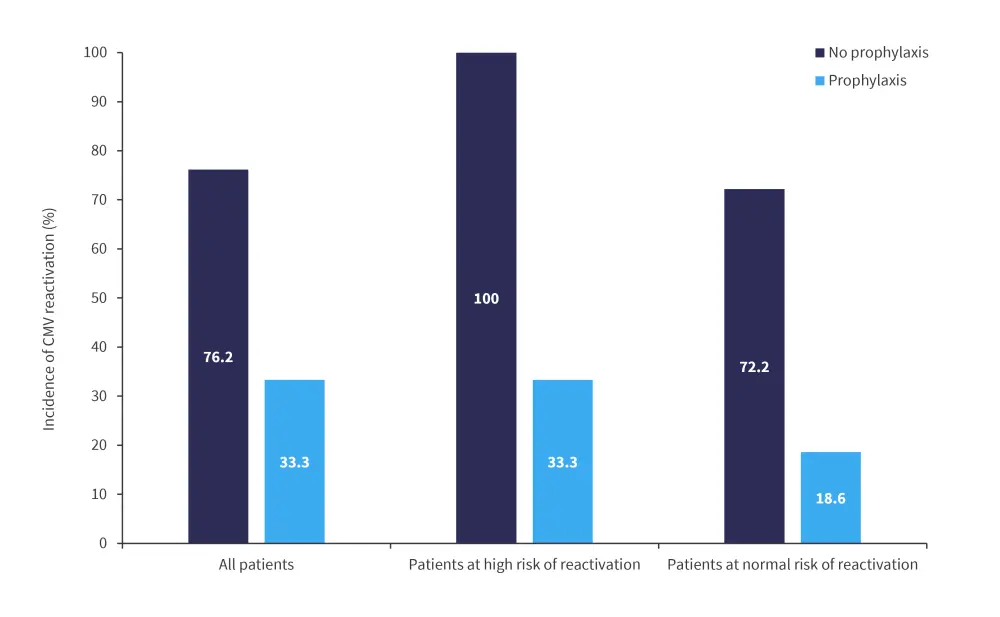

Koch et al.3 conducted a retrospective study into the effectiveness of letermovir, which was approved in Europe in 2018, as viral prophylaxis for CMV. Overall, 48 patients who were seropositive for CMV were included in the study, of which 27 had received letermovir prophylaxis and 21 received no CMV prophylaxis. Patients on prophylaxis received either letermovir 240 mg once daily with cyclosporine as an immunosuppressive, or 480 mg once daily with tacrolimus as an immunosuppressive. The primary endpoint of the study was CMV reactivation (defined as an increase of CMV copies >1,250 UI/ml after transplant) assessed every week for the first 100 days posttransplant, with patients showing persistent T-cell immunodeficiency evaluated past 100 days.

Incidence of CMV reactivation up to Day 200 was significantly lower in patients who had received letermovir prophylaxis, as shown in Figure 5. Engraftment times were comparable between groups and higher toxicity was not seen in the group receiving antiviral prophylaxis.

Figure 5. Incidence of CMV reactivation up to Day 200*

CMV, cytomegalovirus.

*Adapted from Koch, et al.3

The three patients who experienced CMV activation while receiving letermovir were also immunosuppressed due to severe aGvHD. It was found that use of letermovir significantly reduced the risk of CMV reactivation in the first 180 days posttransplant for many subgroups, including patients with an unrelated donor, patients receiving anti-thymocyte globulin, and patients who developed aGvHD.

This study had a relatively small patient size and short follow up, with all patients receiving transplant at the same center; however, it did demonstrate significant differences in CMV reactivation in patients who received letermovir, with the prophylaxis being well tolerated.

Letermovir as secondary prophylaxis4

At the 7th Congress on Controversies in Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapies (COSTEM) 2022, Per Ljungman argued against the use of letermovir as secondary prophylaxis for CMV. Although there is formal definition of secondary prophylaxis, it is used in contrast to primary prophylaxis and would usually occur after CMV reactivation. Although letermovir has been shown to be an effective option as primary CMV prophylaxis, there is no data from controlled studies that demonstrate its effectiveness when given after primary therapy in letermovir naïve patients.

There is also a lack of data on the effect of secondary letermovir prophylaxis on mortality risk in patients with CMV, although the available data suggests it can reduce mortality when compared with a placebo. The risk of patients developing resistance also appears to be low; however, there is also limited data to support this.

Ljungman concluded that letermovir as secondary prophylaxis could be used for some indications, such as for patients with early CMV reactivation who did not previously receive letermovir; however, more studies are required further elucidate whether letermovir is effective in this patient population.

Conclusion

Infection prophylaxis is vital to reduce the risk of bacteremia and viremia in patients who receive HSCT, despite the risks of C. diff infection and antibiotic resistance. However, the study by Alrugaib et al. showed a reasonable rate of C. diff infection in pediatric HSCT patients who had received cefepime prophylaxis.1 Similarly, in the study by Gardener et al., patients who received levofloxacin did not show elevated rates of C. diff infection, with levofloxacin prophylaxis patients showed significantly lower levels of infection than patients who did not receive levofloxacin prophylaxis.2 In patients who received letermovir, viral reactivation was significantly reduced with no significant safety concerns, as reported by Koch et al.

Further large-scale trials, comparing different prophylactics to each other and placebo, would provide more data on the safety of different prophylactic regimes and further elucidate the factors contributing to C. diff infection in patients who receive prophylaxis. Further studies into secondary prophylaxis options are also warranted to produce the necessary safety and efficacy data.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

Which consideration most strongly guides your decision to escalate therapy in SR-aGvHD?