All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional.

The gvhd Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the gvhd Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The gvhd and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The GvHD Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Medac and supported through grants from Sanofi and Therakos. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View GvHD content recommended for you

The use of PTCy for GvHD prophylaxis in adults post-HSCT: Data from a phase II trial

Currently, there is no optimal graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) prophylaxis that is used in combination with reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimen for patients who receive allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) from fully matched donors.1 Antithymocyte globulin (ATG) and posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) are widely used in patients who receive allogeneic HSCT from matched unrelated donors for the prevention of GvHD. However, the effectiveness of using PTCy for GvHD prophylaxis, in patients who receive peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) transplantation from fully matched donors remains unclear.1

Here, we summarize an article by Brissot et al.1 published in Blood Cancer Journal evaluating PTCy vs ATG after RIC allogeneic PBSC transplantation in recipients of fully matched donors (NCT02876679).

Study design1

- This was a randomized, open-label, phase II trial comparing PTCy and ATC in adult patients who received a RIC regimen (fludarabine and 2 days of busulfan) before HSCT from matched sibling donors or 10/10 human leukocyte antigen matched unrelated donors.

- Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive ATG 5 mg/kg plus standard GvHD prophylaxis or PTCy 50 mg/kg/d at Days +3 and +4 plus standard GvHD prophylaxis (Table 1).

Table 1. Treatment regimens*

|

|

Drug (administrated) |

Dosage |

Day/s from HSCT |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Control group |

ATG (IV) |

2.5 mg/kg/day |

-2, -1 |

|

3 mg/kg/day continuously |

Starting at -3 |

||

|

MMF‡ (oral) |

2 g/day continuously |

Starting at -3 |

|

|

Experimental group |

PTCy |

50 mg/kg/day |

+3, +4 |

|

CsA† (IV) |

3 mg/kg/day continuously |

Starting at +5 |

|

|

MMF‡ (oral) |

2 g/day continuously |

Starting at +5 |

|

|

ATG, antithymocyte globulin; CsA, cyclosporine A; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; IV, intravenous; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil. |

|||

- Outcomes included:

- GvHD-free relapse-free survival at 12 months after HSCT (primary endpoint).

- Acute GvHD (aGvHD), chronic GvHD (cGvHD), non-relapse mortality, relapse incidence, disease-free survival, overall survival, cGvHD-free relapse-free survival, and adverse events.

- Health-related quality of life was assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Core Questionnaire and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant.

Key findings1

- In total, 80 patients were randomized to receive PTCy (n = 44) or ATG (n = 45), and 44 and 37 patients in each arm underwent HSCT, respectively

- Overall, the median age was 64 years and baseline demographics were well-balanced between the two study arms.

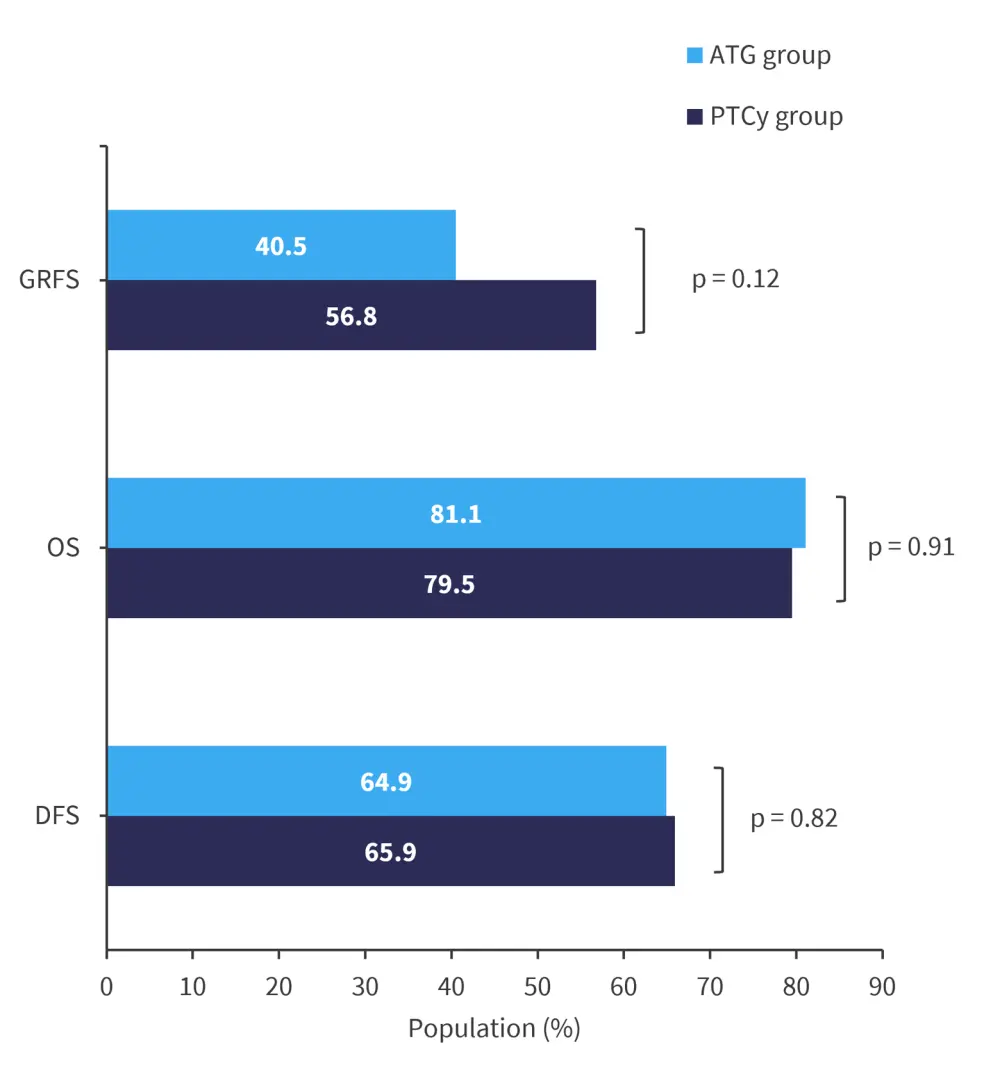

- The primary endpoint of difference in 1-year GvHD-free relapse-free survival between the two arms was not met (Figure 1).

- There were no significant differences observed between the PTCy group compared with the ATG group for DFS or OS (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Survival outcomes at 1-year posttransplant*

ATG, antithymocyte globulin; DFS, disease-free survival; GRFS, graft-versus-host disease-free, relapse-free survival; OS, overall survival; PTCy, posttransplant cyclophosphamide.

*Data from Brissot et al.1

- The median time to neutrophil and platelet count recovery was longer in the PTCy group compared with the ATG group (Table 2).

Table 2. Neutrophil and platelet count recovery posttransplant, with PTCy and ATG*

|

|

ATG group |

PTCy group |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Median time to reach an absolute neutrophil count of ≥0.5 × 109/L |

19 days |

21 days |

p = 0.01 |

|

Median time to achieve platelet count of ≥20 × 109/L |

11 days |

20 days |

< 0.0001 |

|

ATG, antithymocyte globulin; PTCy; posttransplant cyclophosphamide. |

|||

- At 5 years, there was no difference observed in relapse incidence (p = 0.52), cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality (p = 0.57), and cGvHD-free relapse-free survival (p = 0.37) between the PTCy and ATG groups.

- At 6 months, the cumulative incidence of Grade 2─4 aGvHD in the PTCy group was 36.4% compared with 24.3% in the ATG group (p = 0.35). In total, 6.8% of patients went on to develop Grade 3─4 aGvHD in the PTCy group compared with 5.4% of patients in the ATG group (p = 0.81).

- There was no difference in the cumulative incidence of cGVHD at 1 -year in the PTCy group (32.5%) and ATG group (36.1%), and there was no difference in the number of patients requiring systemic treatment between the two groups (p = 0.58).

- The cumulative incidence of cardiac events at 1 year did not differ between the two groups (p = 0.69).

- Within the first month of the study, 72.7% of patients in the PTCy group and 59.5% of patients in the ATG group experienced an infection (p = 0.21).

- Day +30 European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Core Questionnaire scores were lower in the PTCy group vs the ATG group (p = 0.01) with a non-significant trend towards a lower Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant score in the PTCy group (p = 0.051). The scores did not differ significantly at any other time points measured.

|

Key learnings |

|

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

Which consideration most strongly guides your decision to escalate therapy in SR-aGvHD?